The art historian, Wilhelm Worringer, wrote a dissertation in 1906, which became his famous Abstraction and Empathy. […] Worringer stated that modern aesthetics was based upon the behaviour of the contemplating subject. He wrote:

“Aesthetic enjoyment is objectified self-enjoyment. To enjoy aesthetically means to enjoy myself in a sensuous object diverse from myself, to empathise myself into it.”

But Worringer perceived that the concept of empathy was not applicable to long periods of art history, nor to every variety of art.

“Its Archimedian point is situated at one pole of human artistic feeling alone. It will only assume the shape of a comprehensive aesthetic system when it has united with the lines that lead from the opposite pole.

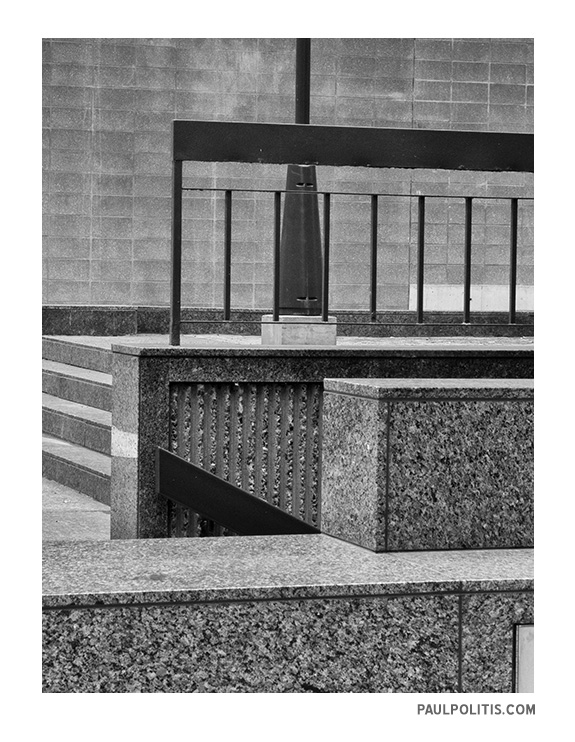

We regard as this counter-pole an aesthetics which proceeds not from man’s urge to empathy, but from his urge to abstraction. Just as the urge to empathy as a pre-assumption of aesthetic experience finds its gratification in the beauty of the organic, so the urge to abstraction finds its beauty in the life-denying inorganic, in the crystalline or, in general terms, in all abstract law and necessity.

Worringer regarded abstraction as originating from anxiety; an attempt by man to create order and regularity in the face of a world in which he felt himself to be at the mercy of unprecedented forces of Nature. The polarity is between trust inNature and fear of Nature. Worringer perceived that extreme empathy led to ‘losing oneself’ in the object – the danger already mentioned in connection with exaggerated extraversion. Geometric form, on the other hand, represented an abstract regularity not found in Nature. Worringer wrote of primitive man:

In the necessity and irrefragability of geometric abstraction he could find repose. It was seemingly purified of all dependence upon the things of the outer world, as well as from the contemplating subject himself. It was the only absolute form that could be conceived and attained by man.

Thus, abstraction is linked with detachment from the potentially dangerous object, with safety, and with a sense of personal integrity and power. This is also the kind of satisfaction which the scientist experiences with his encounters with Nature. A new hypothesis leading to a law which will predict events originates from perceived regularities, from the ability of the scientist to detach himself, his own subjective feelings, from whatever phenomenon he is studying, and, when proven, gives an enhanced power over Nature.

[…]

Abstraction, then, is connected with self-preservation; with the Adlerian, introverted need to establish distance from the object, independance and, where possible, control.

— Anthony Storr, Solitude: A Return to the Self

Storr discusses the work of Howard Gardner. Through studying children’s drawings, Gardner classified children as either patterners or dramatists. Patterners, according to Gardner, “analyze the world very much in terms of the configurations they can discern, the patterns and regularities they encounter, and, in particular, the physical attributes of objects — their colors, size, shape, and the like.” Their formal qualities.

Storr writes:

“For (dramatists), one of life’s chief pleasures inheres in maintaining contact with others and celebrating the pageantry of interpersonal relations. Our patterners, on the other hand, seem almost to spurn the world of social relations, preferring to immerse (and perhaps lose) themselves in the world of (usually visual) patterns.”

I’m reminded of the following quote from Paul Klee:

“The more horrifying this world becomes, the more art becomes abstract.”