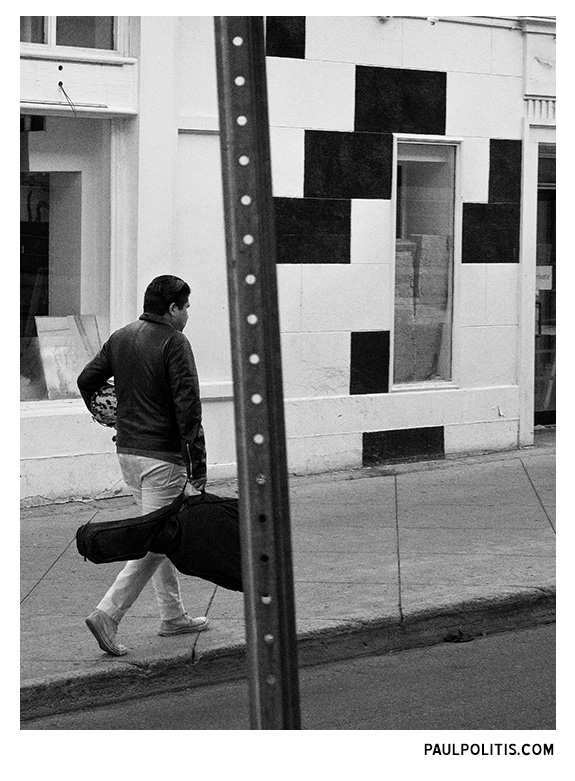

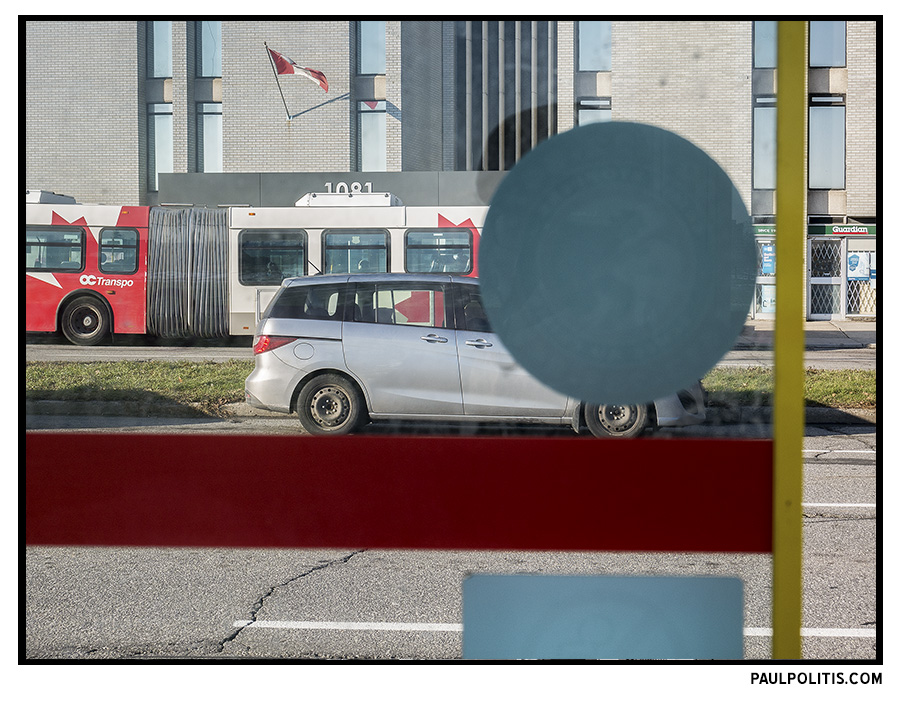

“When three-dimensional space is projected monocularly on to a plane, relationships are created that did not exist before the picture was taken. Things in the back of the picture are brought into juxtaposition with things in the front. Any change in the vantage point results in a change in the relationships. Anyone who has closed one eye, held a finger in front of his or her face, and then switched eyes knows that even this two-inch change in vantage point can produce a dramatic difference in visual relationships.

[…]

In the field […] a photographer is confronted with a complex web of visual juxtapositions that realign themselves with each step the photographer takes. Take one step and something hidden comes into view; take another and an object in the front now presses up against one in the distance. Take one step and the description of deep space is clarified; take another and it is obscured.

In bringing order to this situation, a photographer solves a picture, more than composes one.”

– Stephen Shore, The Nature of Photographs

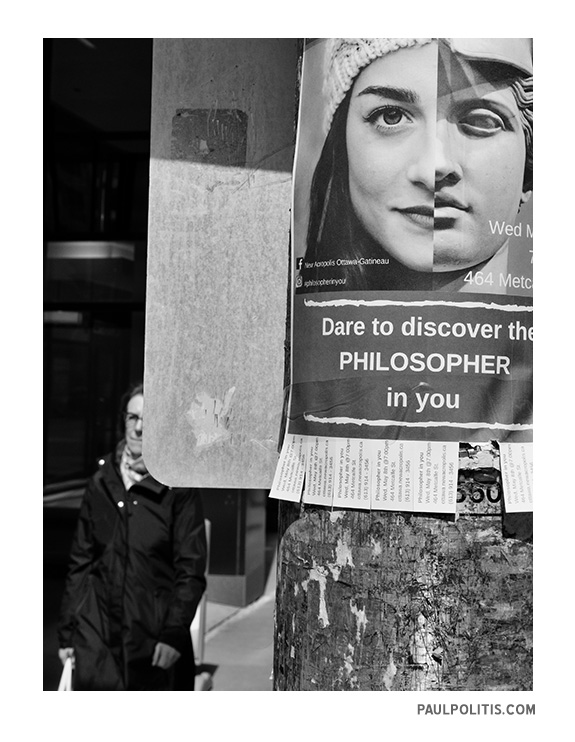

“Immobilizing these thin slices of time has been a source of continuing fascination for the photographer. And while pursuing this experiment he discovered something else: he discovered that there was a pleasure and a beauty in this fragmenting of time that had little to do with what was happening. It had to do rather with seeing the momentary patterning of lines and shapes that had been previously concealed within the flux of movement. Cartier-Bresson defined his commitment to this new beauty with the phrase The decisive moment, but the phrase has been misunderstood; the thing that happens at the decisive moment is not a dramatic climax but a visual one. The result is not a story but a picture.”

– John Szarkowski, The Photographer’s Eye